The Doctors of the Church is my latest review book for The Catholic Company, and I’ll tell you up front why it’s taken me so long to get through it: Because it requires peace and quiet.

I don’t mean like holed-up-in-a-monastery-for-three-weeks peace ‘n quiet. More like, “two to three paragraphs without interruption, and ideally as much as a page or more, all at once, before someone asks you how to spell a word, or where is the milk, or . . .” you know what I mean*. I say this not to discourage the other housewives out there, but rather to encourage you to not give up just because it’s taking you a little longer than a Hardy Boys mystery, or whatever it is you other people read.

What it is: Pope Benedict did a series of talks at his weekly general audiences on each of the Doctors of the Church, and the text of those talks was put into book form. (St. Peter Chrytologus is missing — there was no talk as yet at the time the book went to print. But you get all the others.) Each person gets his or her own chapter, and certain heavy-hitters have double- or triple-sized chapters if it took two or three sessions to cover the topic.

The focus of the talks is on the development of doctrine. Sorry, no fun stories about St. Thomas Aquinas’s family’s colorful attempts to dissuade him from his vocation, or St. Therese’s heroic willingness to eat the peas and fake it that she liked them. You get to be a Doctor of the Church due to your contribution to our understanding of the faith. So that’s where the book focuses: What did this person contribute to our understanding of Christ and of salvation? How did this person respond to the needs of his or her time, and re-present the faith in a way that was needed then, and that continues to be valuable today?

–> A brief biography opens each chapter, and there is enough information to give you a clear picture of the life and times of the individual. There is relatively more biography for lesser-known saints. If you don’t know the general St. Thomas Aquinas story, you aren’t ready for this book yet; but if you never can keep straight all your St. Cyrils and Gregories, the Holy Father has you covered, no worries.

What are the prerequisites?

Before reading this book, you need to:

- Know the broad outline of Church history, and of course that means having a decent grasp of world history as well.

- Be familiar with the who’s who of major saints.

- Have a clear understanding of Church teaching.

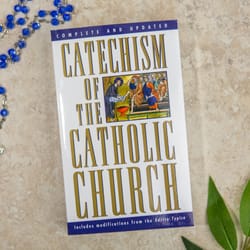

- Be comfortable with technical language at about the level of The Catechism of the Catholic Church. This one:

If that’s not you, be patient. Come back to The Doctors later. Because the focus of the book is specifically on doctrine, and on the development of doctrine, this is a little harder of a book than some of the other collections by the Holy Father.

Who is this book for, and what good is it, anyway? I recommend this book if you . . .

. . . Want an introduction to the topic of Development of Doctrine. When read cover to cover, in sequence, this is an excellent first look at how the faith has blossomed over the centuries.

or

. . . Need a reference book on hand for all your Doctors of the Church needs. Great resource for catechists and others who need to quick know something intelligent about obscure-but-essential saints. Each chapter stands on its own, and I found this to be very useful in preparing for class.

or

. . . You want a devotional that is built around reflections on theology and the lives of saints. (Don’t laugh you Prayer of Jabez people, some of us like this stuff.) You could either work through it a chapter at a time, or just have it on hand to browse at random when you need a little retreat into that happy place where you get to think about this stuff.

Verdict: Well of course, it’s excellent. If you are the target audience, there’s nothing else like it. Worth the effort to work through it, not because then you’ll get to sit with the cool kids (though you will), but because even if the distractions of your vocation mean you can’t read through it quickly, it’s very meaty and satisfying. A sure preventative against brain rot, and not so bad for your soul, either. Great book.

***

Thanks again to the kind people at the Catholic Company, who would like me to tell you that not only do they do a work of mercy providing good books for bloggers in exchange for nothing other than an honest review, they are also a great source for a baptism gifts or first communion gifts.

*No family members were injured in the writing of this post.