Fourth of July a fellow on a bicycle saw me photographing the parish war memorial in Sigolsheim. He asked me where I was from, and I told him the US, and he proceeded to thank me for coming. Periodically throughout the conversation he thanked me again, and before leaving he repeated merci about seven times. There was a reason for that, which I’ll get to.

A typical way of inscribing a war memorial in France is to write Mort Pour La France, but in Alsace that’s not usually the case, for the obvious reason. A Nos Morts is the common alternative that glosses over the whole question of whom you died for, and gets to the point: You died. Here’s the memorial outside the parish church in Uffholtz, A Ses Enfants Victime de Guerre:

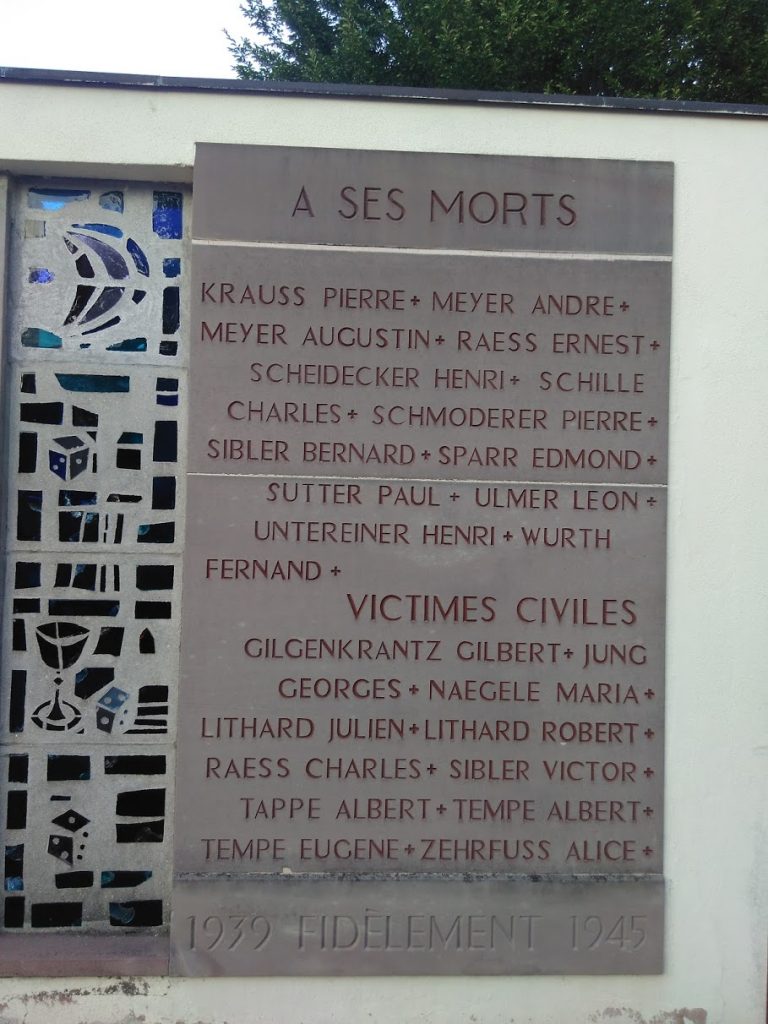

Here’s Sigolsheim, in two parts. You’ll notice WWII was disproportionately bloodier than WWI for Sigolsheim, including a significant number of civilian deaths:

That’s because the Nazis dug in and held hard, and a giant set of battles were held in the village itself, which you can read about in extensive detail here. When German empires decide to assert themselves, annexing Alsace is the default method. (And why not throw in Lorraine while you’re at it?) This is the reason that headquartering European postwar peace initiatives in Strasbourg is so symbolically important.

Persuading the Third Reich to retreat from Alsace was bloody-difficult, and American soldiers played a major part in that work, which is half the reason the fellow on the bicycle was so profuse in his thanks for my coming to visit and taking an interest in the local history.

Here’s the village of Kayserberg’s thank-you plaque:

The American flag flies above Sigolsheim at this war memorial:

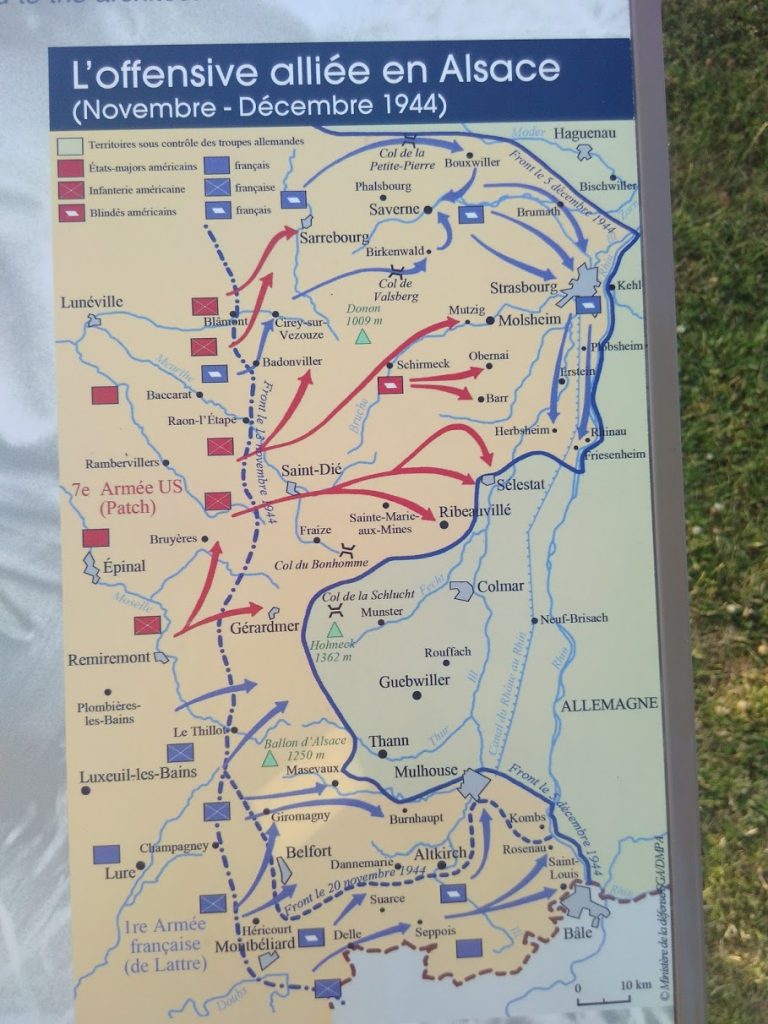

Everything in red on this map of the the Allies’ Alsatian offensive is American forces:

American soldiers aren’t buried at the Sigolsheim memorial (there are American war cemeteries elsewhere). There is a cemetery, though, for the French forces killed in battle in the immediate vicinity:

You’ll notice in the picture above that most of the graves are crosses, and a few are not. Here’s a detail of the rounded-rectangle gravestone in the bottom right:

It would obviously not be kosher (pun intended) to use a cross to mark the grave of a Jewish soldier. It is not only American and native-born French soldiers, however, who were instrumental in liberating Alsace. The Zouave soldiers buried at the Sigolsheim war cemetery have grave markers like this:

In other words, if you’re grateful France is free, don’t just thank an American — thank a Muslim. Ah, but how much did those Muslim soldiers contribute? About like this:

As the video shows, the cemetery is built on a hill in a half-circle, and the graves are laid out in four equal sections. The two flanking sections are Muslim graves, and the center two sections are mixed Christian and Jewish graves. History is complicated.

Whether the fellow on the bicycle would have thanked me so profusely if I were a North African tourist I couldn’t say. I’m not one. What we do get mistaken for in Alsace is German tourists. We look the part and come by it honestly, if distantly. German tourists come up and ask us directions, in German, which doesn’t get them very far. Locals either attempt to speak German with us or else apologize that they have no German (neither do we — how about French?).

So here are a couple of my cute German kids walking towards the gate out of the KL-Natzweiler Concentration Camp, up near the village of Struthof in the Vosges mountains:

People who didn’t walk out might have died here in the cell block:

At which point they would have been incinerated in this crematorium:

When we talk about concentration camps and the evil of the Nazi regime, the usual thing is to tell kids, “If you were Jewish . . .”

Struthof, as KL-Natzweiler is often called locally, is different, in that it was chiefly used not for eugenic purposes but for those who resisted the Nazi regime. Thus more to the point for our nice German boy in the photo above: Let’s talk about the draft.

His great-grandfathers were all about his age (17) at the start of World War II. They had the luxury of being second- or third- or more-generation Americans, and they all volunteered and served in the War for the US. It was not a difficult decision. They were the age your brother is now, I told the girls.

Had he been seventeen and American, the boy would have signed up too, I’m fairly certain. But what if he had been seventeen and German — which, after a week of being mistaken for a German tourist (or an Alsatian local), is not at all a stretch of the imagination? He would have had to decide between going into the Nazi army, or going to Struthof.

Which is why a guy on a bicycle, about my age, resident of a nearby village, passing by on July 4th evening outside the war memorial in Sigolsheim couldn’t stop thanking me for being an American who came to Alsace. He saw I was interested in history, and started suggesting sites. “Do you know there’s a US war memorial up on the hill?” he said.

Yes. Just came from there, actually.

“And have you seen the three castles down by Eguisheim?”

Yes. And the other one, and some other ones . . .

“Let’s see, so maybe you should go to –”

“Well actually,” I tell him, “we only have a few more days here. We’re going to try to go to Mont Sainte Odile and to–” I try to remember the name — “Struthof–?”

He stops. “Oh. Struthof. That’s hard.”

I know.

But you can’t really appreciate the significance of the war unless you know the whole story.

“The concentration camp,” he says. “Struthof.”

“Yes.”

“My grandfather was there.”

Flowers at the Sigolsheim war memorial, in bloom on July 4th.