When I first showed up in France as an exchange student in high school, my host sister asked me, in English, “When you speak French, do you think in English first and then translate, or do the words just come?”

At the time I’d had two years of high school French — just enough to make French people want to try out their English, that was not something French people of that era were too excited about doing.

I wasn’t sure. I was somewhere in between, after a couple weeks in-country, and a lot of hours spent passing notes in bad French to my friend in geometry class the year before.

Brendan at DarwinCatholic writes about the challenge of being stuck in translation-mode as a student of German.

He is almost certainly paying the price that comes with being analytical and diligent. I am neither (not to the degree he is, anyhow), and so I strongly favor a different approach to learning languages that will leave you with horrible holes in your grammar, but significantly better reading fluency than a slacker like me could ever deserve.

Here is what I told Brendan to do, and if you are in his shoes, it might help you, too.

#1. Relax.

This is not personal advice, it is mechanically necessary for reading fluency.

There are different parts of your brain that carry out different tasks.

If you are deep in analytical thought, the part of your brain that lets words flow effortlessly gets put on the back burner. Even though my French is fluent (not perfect, just fluent), if I’m nervous or distracted by contrary thoughts, it’ll bog down. Here’s a real thing that happened to me once which made this clear:

For about five minutes back in the ’90’s, I studied Italian. That’s like an actual five minutes, not a metaphorical five minutes — my husband had some Italian books I was putting away. I run into Italian here and there on the internet because I’m Catholic and I read Amy Welborn, and since I’ve studied other romance languages, it’s something that kinda sorta makes sense. So I can sometimes read easy Italian pretty well, if it’s a topic that I’m familiar with, heavy on the cognates.

Thus one day I was reading this magazine article in Italian, no big, hey, who doesn’t read magazine articles in Italian? Totally rocking it.

It was religion or something, or else I got to thinking about religion or something, and I put the article down and set my brain to articulating a series of arguments on a tricky topic. When I went back to the article with my analytical-brain in high gear? It was all gibberish. I literally went from reading fluently to having to painfully pick apart word by word — and the latter is not a good technique in a language you’ve never formally studied.

So anyway, I learned from then on that totally relaxing is the key. Pour yourself a drink. Think about picturesque villages and parts of the world where decent coffee is a birthright, and then amble on in like you don’t really care. Makes a big difference.

#2. Gorge on the spoken word.

Part of developing fluency is getting the rhythm of the language into your head. When you learned to speak your native language, you began by spending a year and some just listening to people around you say things you mostly didn’t understand. The first part of it you were listening underwater, for goodness sake.

True story: My eldest came into this world crying like a normal newborn does. Newborns have a distinctive just-fell-off-the-turnip-truck amateur quality to the way they cry. #2 gestated in an environment flooded with her older brother’s loud and emphatic toddler tantrums echoing into the womb. She thus entered this world not crying like some neophyte, but with all the intonation and rhetorical sophistication of a veteran whiner. Woken in the middle of the night by some child carrying on, I could not know without looking whether it was the toddler being himself, or the newborn sounding eighteen months older than she was.

To get the rhythm of a language into your head, you have to swim in it, bathe in it, and guzzle it down with supper every night. Understanding all the words is not the important thing at first.

–> The inner fluency you gain from hearing language more sophisticated than you have personally mastered is part of why read-alouds are so important to helping young children learn to read.

#3. Practice saying the patterns.

Brendan writes about the grammatical construction in German that’s giving him a hard time. To get over the hump, what you have to do is use that construction. Except that whoa, he’s only a couple years into this. So what you do is learn some phrases and sentences of daily usefulness that incorporate the tricky grammar.

He has some children on whom he can inflict his practice sentences, if only he chooses commonly used expressions, such as whoever changes the baby’s diaper doesn’t have to take out the trash. Or whatever else might be applicable.

Languages are collections of patterns. Once you have a basic pattern into your head, subbing out a noun for a noun or a verb for a verb is pretty easy.

–> This is part of why building words with magnet-letters, building sentences with flashcards, and playing word games where parts of words or sentences are interchanged are so helpful to learning to read.

Edited to add: Erin at Bearing Blog has a superb technique for working odd language patterns. I do this a lot in my head, but she’s methodical and diligent like Brendan is, so she does it for serious.

#4. Read lots and lots of easy stuff

When I say easy, I mean ridiculously easy. Pick topics that are heavy on cognates of vocabulary you already know, and covering topics you already understand. (I recommended economics, history, politics, and religion for Brendan.) Read these things in short sessions. By short I mean: About the size of a paragraph in a church bulletin, or an article in a tourist brochure, or R.R. Reno’s paragraph-sized observations at the back of the print edition of First Things.

Edited to add: Reader Bill Hauk points out that children’s books are excellent for this. I couldn’t agree more.

Be warned that micro-messages, such as billboard advertisements, are usually not that helpful. They tend to require lots of inside cultural knowledge and grammatical sophistication. You want a big enough chunk of text that you can miss a few words here and there and still know pretty much what was being said.

These are not a complete method for learning a language.

Brendan’s already got the grammar side of things under control, and I bet he pays attention to spelling too. For building technical translation skills, the sorts of training I’ve described here will basically ruin you. You’ll absorb the language straight through the skin, and if you are reading anything produced by a half-decent writer, the thought of exchanging something said so perfectly into some pale imitation will become anathema. No translator will quite get it right again, ever, as far as you’re concerned.

But you’ll be able to read, so that’s good.

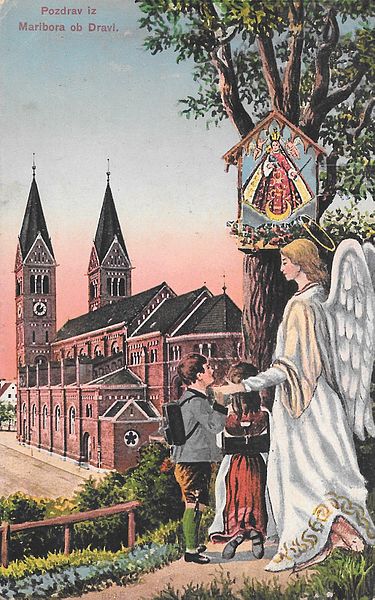

La petite Venise, Colmar, France. By HNH (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.