In the past few weeks I’ve gotten to visit two of the Diocese of Charleston’s newest parish church buildings. St. Paul the Apostle in Spartanburg and St. Mary Help of Christians in Aiken are both well worth a look. (Our Lady of the Rosary is still on my sightseeing wish-list; meanwhile, for something fun, go see the stained glass at St. Andrew’s in Myrtle Beach — there is more information about those windows available at the church when you visit. If you’re off the beaten path, Our Lady of Lourdes in Greenwood is charming and bright — the photos don’t do it justice.)

We are fortunate to live in a diocese where good design is flourishing. I don’t for a moment wish to naysay any of the hard work and sacrifice that went into creating these beautiful new buildings. On the contrary — I am grateful beyond expressing.

But let’s not delude ourselves: The very existence of some (not all) of this new construction should be an elegant, delightful, but shocking warning sign.

The Myth of the Flourishing Parish

Let’s look at St. Mary’s as a case study. The original St. Clare’s chapel, now devoted to perpetual Eucharistic Adoration, was succeeded by the first St. Mary’s Help of Christians parish church early last century. You can read an insightful history of Catholicism in the region — dating back to the 16th century — here. The historic St. Mary’s parish church is still in use. It wasn’t replaced because it was no longer habitable. It was replaced because there were too many parishioners to fit into the building.

This sounds like a good problem, right? It is, in a way.

It would be more accurate, however, to say: There were too many parishioners for the number of priests.

The Catholic population in Aiken, SC, as with the rest of the diocese, has grown significantly due to retirees moving south (we get your empty church parts to refurbish our buildings), professionals moving here from other parts of the United States, immigrants arriving from around the world, a certain number of conversions, and of course old-fashioned human reproduction. Some of this represents spiritual growth; some of it is just other parts of the world sending us their Catholics.

But regardless of the cause, an unavoidable fact is now set in stone, brick, and concrete: We are not producing priestly vocations in adequate numbers.

A Faith Not Even Worth Living For

The Diocese of Charleston has a good vocations program going. There’s always room for taking any initiative to the next level, but over the past twenty years the diocese has gotten conmendably serious and hard-working about reaching out to would-be seminarians. We do have vocations flowing. We have some superb new priests, and more on the way. Fr. Jeffrey Kirby didn’t receive the state’s highest civilian honor for nothing.

Still, the arithmetic doesn’t lie. Some parishes are on fire with the faith. Some Catholics — in every parish — are wildly in love with Jesus and have the fruit to prove it. But mostly we have to make larger buildings because we have pewsitters who love the pews, but who wouldn’t want to get carried away with any craziness. Catholicism is legit here these days. Church-going is civilized. If you’re nicely married, it’s a wholesome place to raise the kids.

We feel good about our faith and we do good works, but it’s not the kind of thing you’d really give your life over for. We pat ourselves on the back if we get the teens to Adoration for ten minutes. We’re wildly excited if a young couple gets married in the Church — the idea that most young adults would remain Catholic after high school is a rich fantasy. Some statistics, via Brandon Vogt:

- 79% of former Catholics leave the Church before age 23 (Pew)

- 50% of Millennials raised Catholic no longer identify as Catholic today (i.e., half of the babies you’ve seen baptized in the last 30 years, half of the kids you’ve seen confirmed, half of the Catholic young people you’ve seen get married)

- Only 7% of Millennials raised Catholic still actively practice their faith today (weekly Mass, pray a few times each week, say their faith is “extremely” or “very” important)

- 90% of American “nones” who left religion did so before age 29 (PRRI)

- 62% leave before 18

- 28% leave from 18-29

If you’re not even Catholic, you are highly unlikely to become a Catholic priest.

Old Warning Signs

For as long as I’ve been talking to catechists and faith formation leaders, the refrain has been the same: “The kids in religious ed don’t even go to Mass.” Some do, of course (mine, and quite a few others I know), but a surprising number of children are dropped off for CCD but never taken to Mass. The situation is so dire that some parishes have resorted to requiring children preparing for sacraments to provide hard evidence they attend Sunday Mass, such as getting a bulletin signed.

Here’s another example by way of a personal story. My daughter’s would-be confirmation sponsor is an ardent young Catholic well known by many in the local Catholic community. As we put together paperwork, however, we discovered that due to an oversight when the family purchased a new home, they are not presently registered at the parish they attend most. We’ll get it all straightened out one way or another, don’t be scandalized because there is no scandal.

But the underlying situation is this: It is now the rule that the way we “prove” someone is a “practicing Catholic” is via a set of papers and financial transactions. Get registered, turn in collection envelopes, and you qualify for a “Catholic in Good Standing” letter. The idea that one could simply be a faithful Catholic known in one’s community is utterly foreign to the present practice.

What if you trusted people when they said the godparents or sponsor were good Catholics? We have come to fully expect people would outright lie as a matter of course.

Thus we live with a different set of lies. We as a Church are so alienated from any sense of real community that we depend on bureaucratic proxies that supposedly indicate a practice of the faith, but everyone knows that they don’t. Everyone knows that teenagers go through confirmation to make their parents happy, and then drop out at first opportunity. Everyone knows that the confirmation class is composed of kids who last attended Mass at their First Communion. Everyone knows that when we teach the Catholic faith assiduously, the kids whisper to themselves, right there in class, which parts they think are bunk.

The parts they think are bunk are almost invariably the parts their parents likewise think are bunk. The Catholic Church is the stronghold of people who know how to shut up, smile, and get along.

Repeating Ourselves to Death

Any student of Church history can attest that things have always been shockingly bad. The behavior of Catholics is the incontroveritble evidence that God must be holding this institution together, because it sure isn’t us. That is not, however, an excuse to keep on behaving badly.

I write this today because I’m concerned that our beautiful new buildings will lull us into continued complacency. We will persuade ourselves that what we’ve been doing is working.

It isn’t.

The buildings themselves cry it out. We shouldn’t have mega-parishes. We should have enough priests that when the parish overflows, we’re ready to form a second parish nearby.

The lack of priests isn’t some mystical aberration. God isn’t suddenly pleased with the idea of men exhausted from administering multiple parishes and saying half a dozen masses in a weekend and having to rely on collection envelopes to know who comes to Mass because they couldn’t possibly meet all the parishioners they are supposed to be pastoring. Nonsense.

We have no priests because we are very good at getting along and forming lovely clubs, but we are terrible at being Catholic.

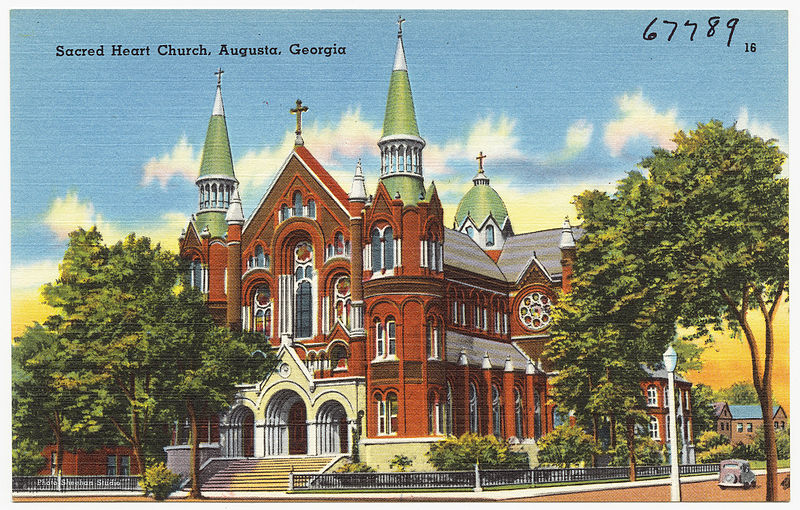

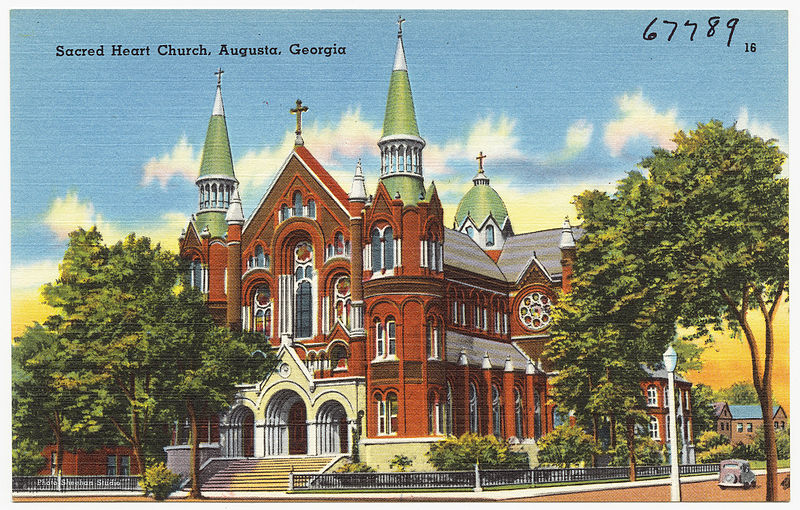

If we don’t change this, St. Mary’s beautiful new building in Aiken will enjoy a brief sojourn as a Catholic Church, and then go the way of Sacred Heart across the river, no longer a church, now just a lovely but Godforsaken building.

Artwork: Postcard courtesy of Boston Public Library (Sacred Heart Church, Augusta, Georgia) [CC BY 2.0, Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons